Domicile

Domicile

High ceilings and open minds

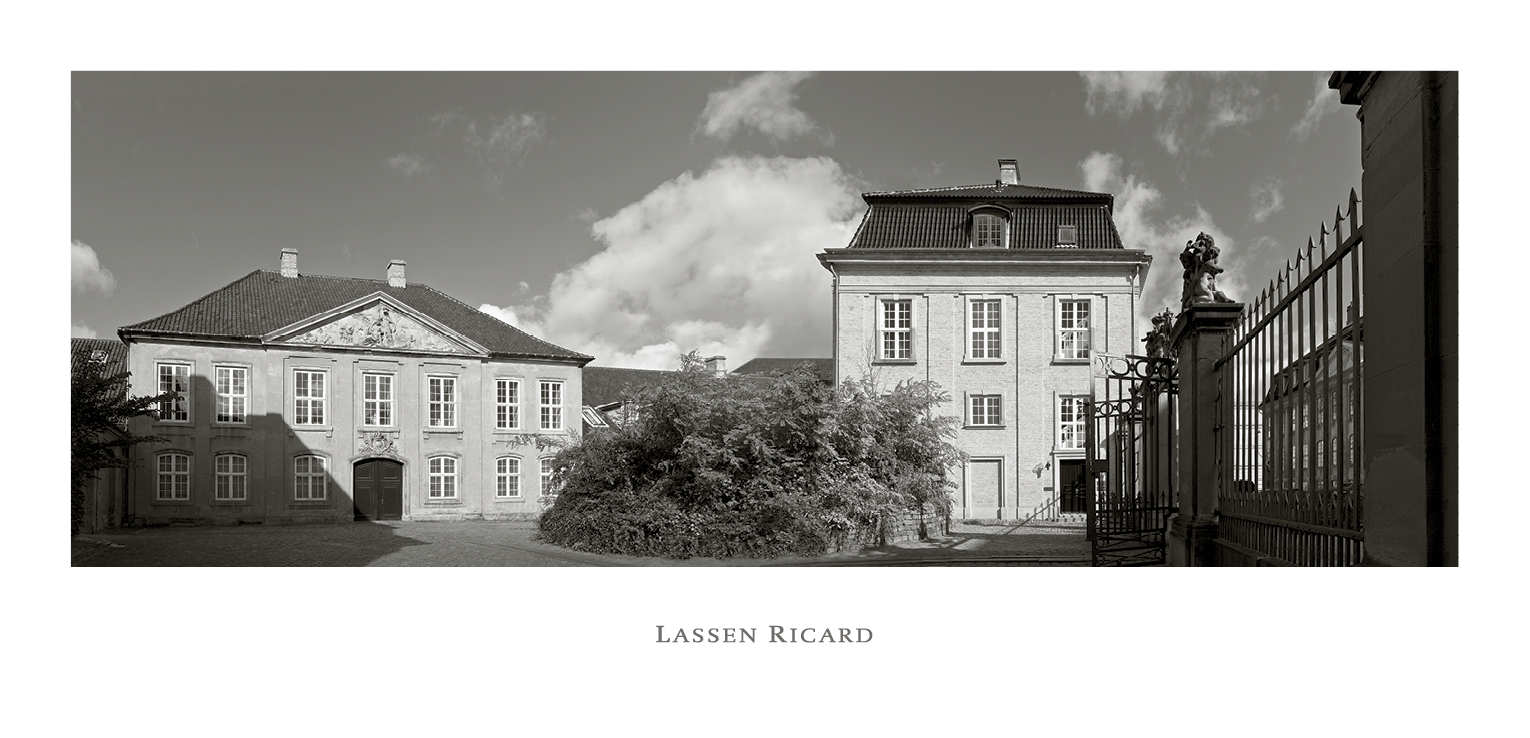

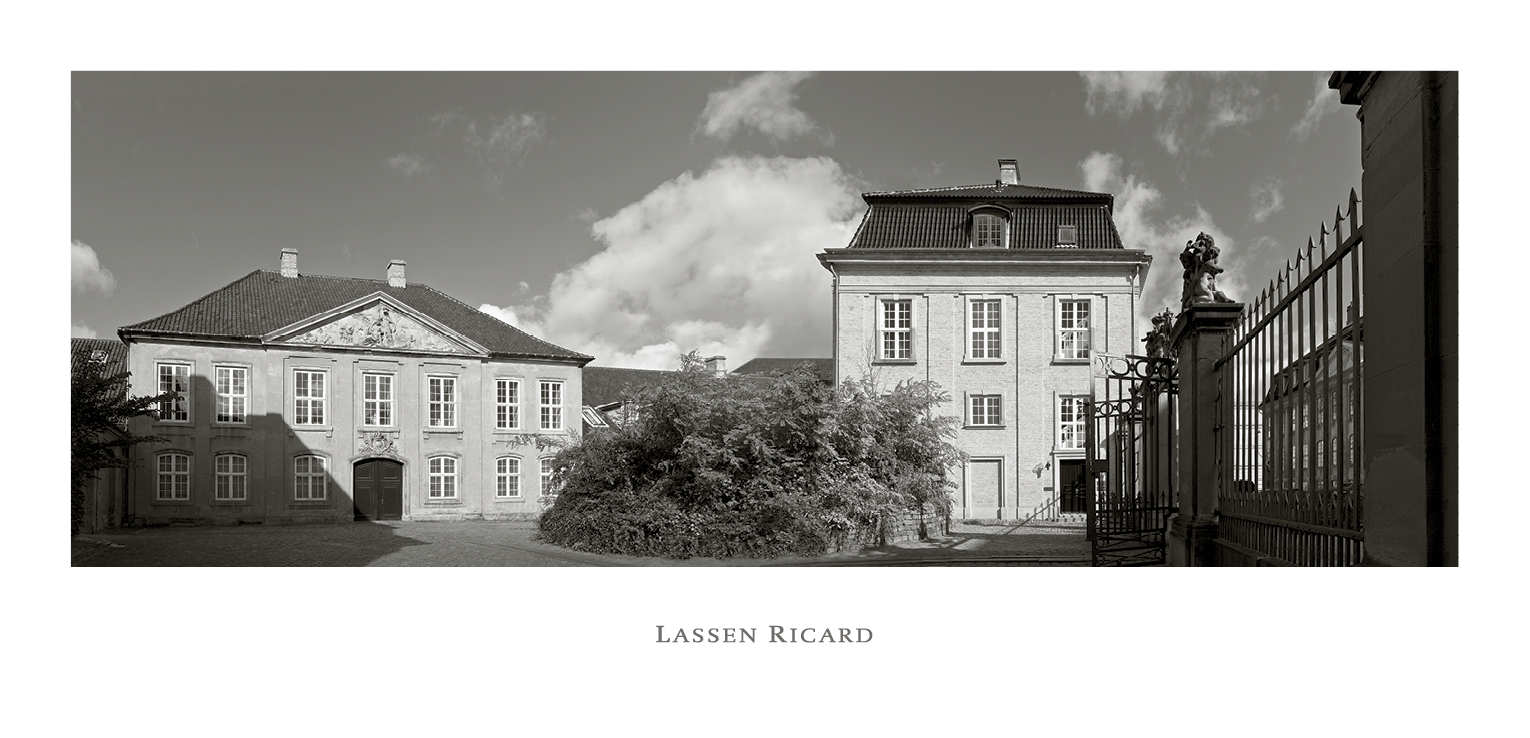

The house at 31 Amaliegade, our base since 2002, provides the framework for our day-to-day work. The beautiful, yet simple surroundings create a harmonious work environment and a sense of belonging.

Domcile

Our domicile is located at 31 Amaliegade in one of the four baroque mansions built round the former Royal Frederiks Hospital, which now houses Copenhagen’s design museum, Designmuseum Danmark. Nicolai Eigtved oversaw the early construction of the hospital, and after his death King Frederik V delegated the completion of the buildings to Lauritz de Thurah, the architect who also built the Hermitage Hunting Lodge.

Situated at the heart of Denmark’s contribution to world architecture, the Frederiksstaden district, the hospital was inaugurated in 1757, and the elegant domicile building today offers views of the Copenhagen Citadel, the Gefion Fountain and the Amalienborg Palace.

With its streets and avenues, church, royal palace and patrician houses, the Frederiksstaden district unfolds from its centre: the Amalienborg Palace Square with Saly’s equestrian statute of Frederik V. Everything is in its right place, forming a natural synergy - and the proportions of height and space have a human dimension.

This variation and unity, from the grand squares to the details of a window or a street corner, is the realisation of a key inspirational and aesthetic concept. Everything is in order.

Domicile

Every year, we send Christmas cards to business connections, associates and friends of Lassen Ricard. These Christmas cards illustrate the story of our domicile in text and image. View all of them below.

2023

Christmas card 2023

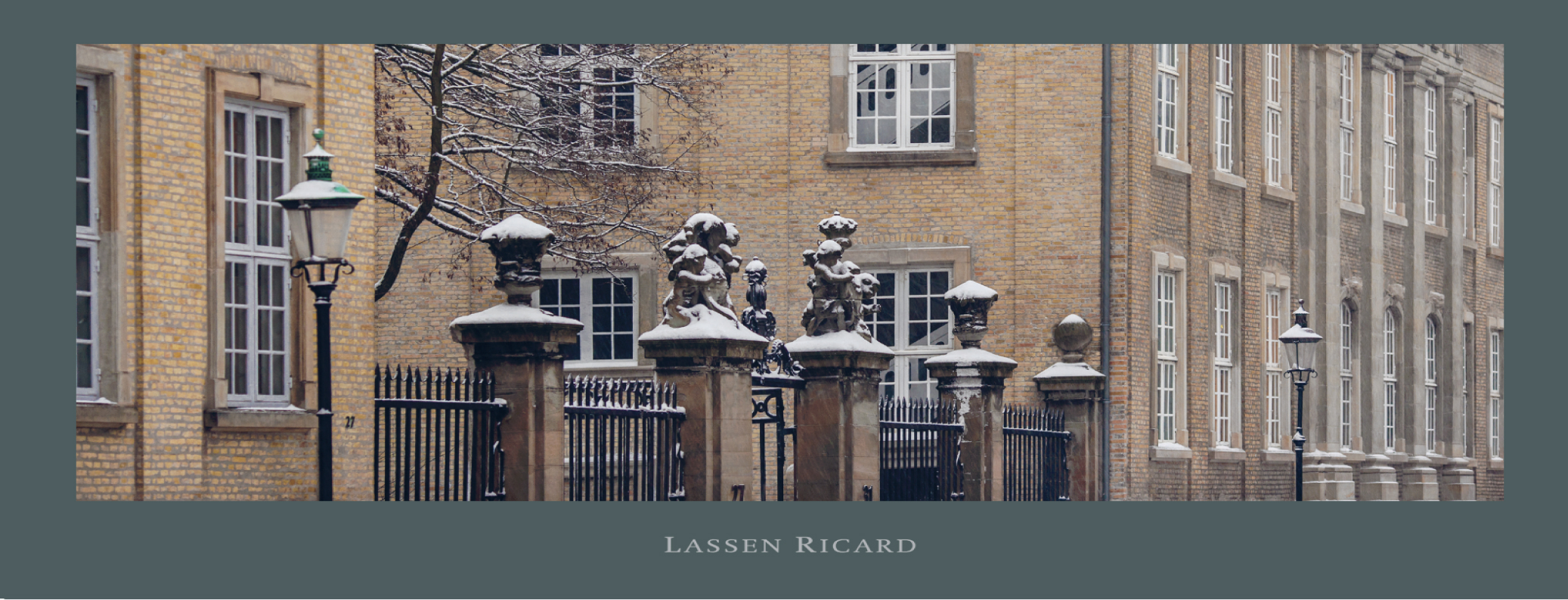

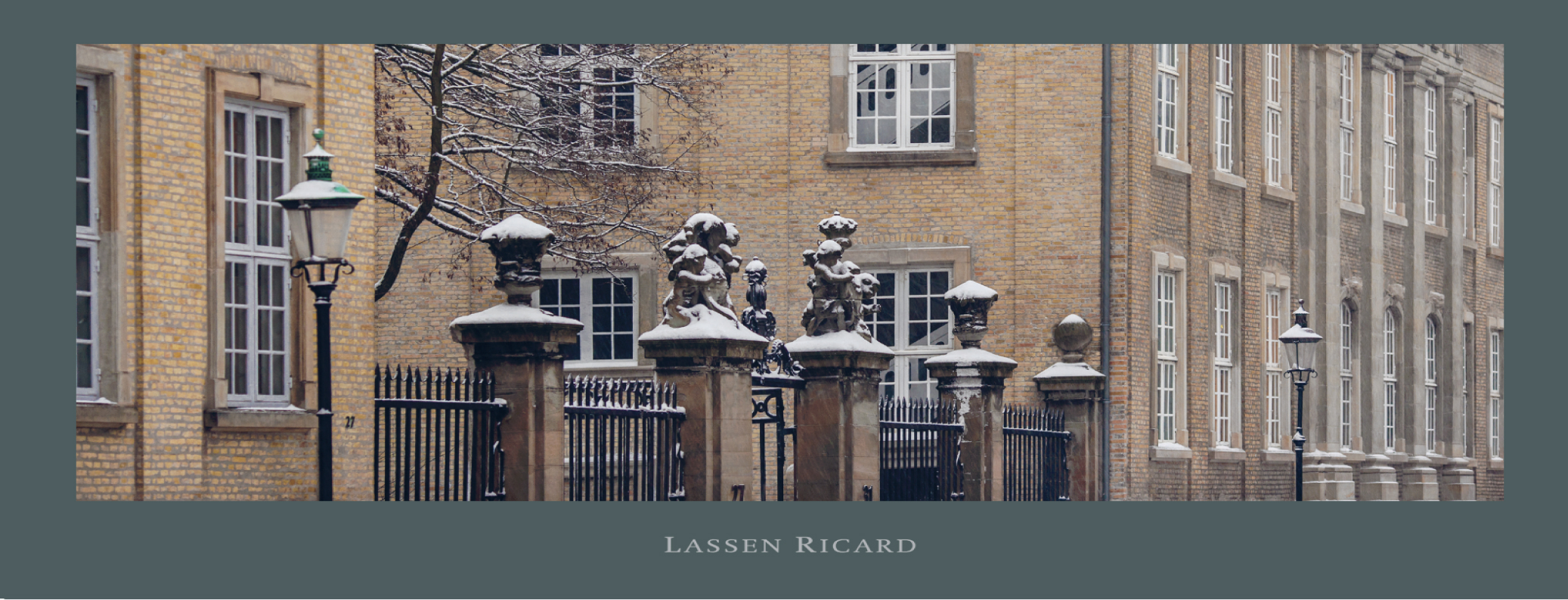

The Royal Frederik’s Hospital, where Lassen Ricard is domiciled, was first and foremost the work of two great architects. The main four-wing building with two central pavilions was created by Royal Master Builder Nicolai Eigtved (1701-54), while the four front buildings facing Bredgade and Amaliegade are the works of Master Builder General Lauritz de Thurah (1706-59). In literature, the two architects are often described as sworn enemies. That is an exaggeration, but each had his own ideas about building. Eigtved was most in step with his time, as he had developed a taste for the latest architectural style, Rococo, during his training as a lieutenant in the Engineering Corps in Saxony. He stayed faithful to that style when, in 1751-54, he designed the low buildings around the two central pavilions with their characteristic hipped roofs. At the time of his death in 1754, plans had been made for the construction of four front buildings, albeit not one storey high, as designed by Eigtved, but with two storeys to gain more space. Thurah, newly appointed Master Builder General after the death of Eigtved, was in charge of realising these plans. In contrast to Eigtved, he had developed a keen interest in the popular architectural style that could be traced back to the

architect of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome, Michelangelo, and reached its zenith in Baroque architecture in the seventeenth and early eighteenth century. The front buildings were therefore designed in a style very different from the main hospital buildings. To add spice to the story of the animosity between the two architects it has been claimed that the front buildings wreck Eigtved’s delicate structures. That is not true. With his rather more massive mansard-roof buildings, Thurah created an impactful contrast to Eigtved’s elegant design, thus making the buildings as a whole highlight one of the great qualities of Baroque architecture: the masterful use and strong interplay of contrast. Thurah was also a master of connecting buildings by using railings and lattices, which is illustrated by the magnificent fences he created along Bredgade and Amaliegade. The fences are characterised by beautiful brick pillars featuring sandstone vases and coat-of-arms cartouches linked by elegant iron railings.

____

Text: Claus M. Smidt, MA art historian

Photo: Jens Markus Lindhe

SEASON’S GREETINGS AND A HAPPY NEW YEAR

2022

Christmas card 2022

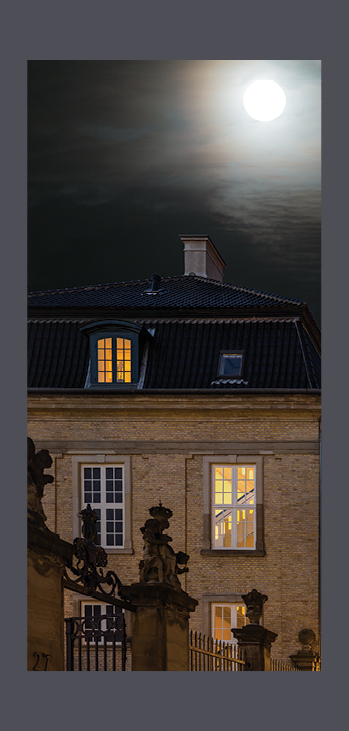

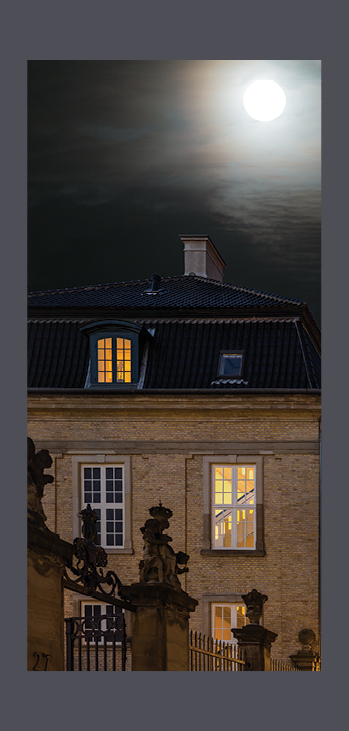

Where does the street Amaliegade go on an evening in December? Even the most ordinary things look remarkable in this enchanting light that shines from the streetlamps and streams out from the mansion that was once Frederik’s Hospital. It is in all the windows – and it comes from Christmas.

But where does Christmas come from? Everywhere, for Saint Nicholas wore green and came from Turkey. Santa Claus had to become that round, red figure with a white beard selling Coca-Cola in the United States before he came down our chimneys in Denmark.

What about the Christmas tree? It was imported from Germany – just like the tradition of decorating it with naked candlelight. Candles were lit on the Lehmann family’s tree in Copenhagen in 1811. The fire brigade was called to put out the blaze.

We stand around the tree and sing ‘Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht’ without even knowing it. And the first thing we made our own from Germany after the Second World War was the Christmas calendar, which was printed in a magazine as ‘Adventskalender’.

Yule goats turn up from Sweden, and when we run through our rooms and sing ‘Now it’s Christmas again’, it is just as Swedish as the Santa Lucia procession, with the bride who carries forth the light on the thirteenth of December.

Our Christmas gathers the whole world, and the celebration reminds us that we only exist because of one another. We light the candles on the tree together. It is our communal life that flows through all rituals and fills the Christmas stockings with feelings and gives the gifts their meaning.

That is the Christmas that comes out from the old mansion that Lassen Ricard calls home and lights the windows up on evenings in December.

____

Text: Knud Romer

Photo: Jens Markus Lindhe

Merry Christmas and

happy New Year!

2021

Christmas card 2021

HISTORY'S GIFTS

There is time – and then there is festive time. The first drives forward with the clock and disappears without our giving it a thought. The second returns and repeats, year after year, with devotions and memories: history. Here it’s not about passing time. On the contrary, the more time you allow yourself, the more you will receive – and if you linger among objects, they will open up to you like Christmas gifts.

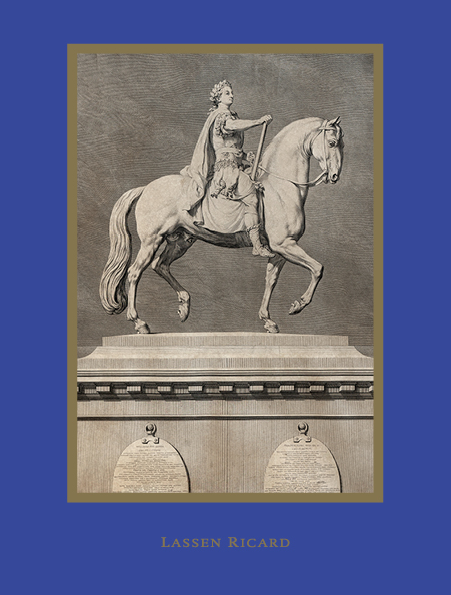

You can just keep on unwrapping them. So it is for the copper plate print on the wall of Lassen Ricard’s offices. It depicts an equestrian statue of Frederik V, which stands just a little way down the street and carries a piece of world history right in the heart of Frederiksstaden. The etching was printed in Paris in 1770 and is a masterpiece of Danish graphic art. It was realised by Johan Martin Preisler, who brought the best of his artist-upbringing in Nuremberg and his career in France with him to Denmark.

The equestrian statue itself in Amalienborg Courtyard is the work of Jacques-François-Joseph Saly. He was the great horse-sculptor of his day and arrived in Denmark from France in 1753.

It took fourteen years to complete from the studio in Charlottenborg, and then in 1764 the times’ finest bronze caster, Pierre Gors, another Frenchman, arrived. He ordered the roof to be removed from the old canon foundry to make room for a bigger kiln. And four years later they were that far at least. 20,000 kilos

of molten bronze were poured into the cast. That took all of three minutes. And then two days for 200 able seamen to drag the 22 ton statue on a sledge from Kongens Nytorv to Amalienborg Courtyard.

In the end it cost more than the four Amalienborg palaces combined. And who paid for it? The Danish Asiatic Company, which had thrived on trade with China, and whose president, who came from Meckelenburg, was Court Marshal of Denmark under Frederik V and Lensgreve, the highest noble rank: Adam Gottlob Moltke.

The statue was erected to mark the occasion of the 300th anniversary of the Oldenborg bloodline’s ascension to the Danish throne: a European dynasty with roots in northern Germany.

So met east and west, north and south, across borders and nations to create one of the world’s finest equestrian statues.

There is always more than you might have imagined. You can walk past the print on the wall or give yourself the time for its history. That is what sets things into motion and gives them life – so that Frederik V can ride away.

Anything is a gift and will enrich you, if you make the effort to unwrap it. It is up to us what lies beneath the tree.

___

Text: Knud Romer

Photo: Jens Markus Lindhe

SEASON’S GREETINGS AND A HAPPY NEW YEAR

2020

Christmas card 2020

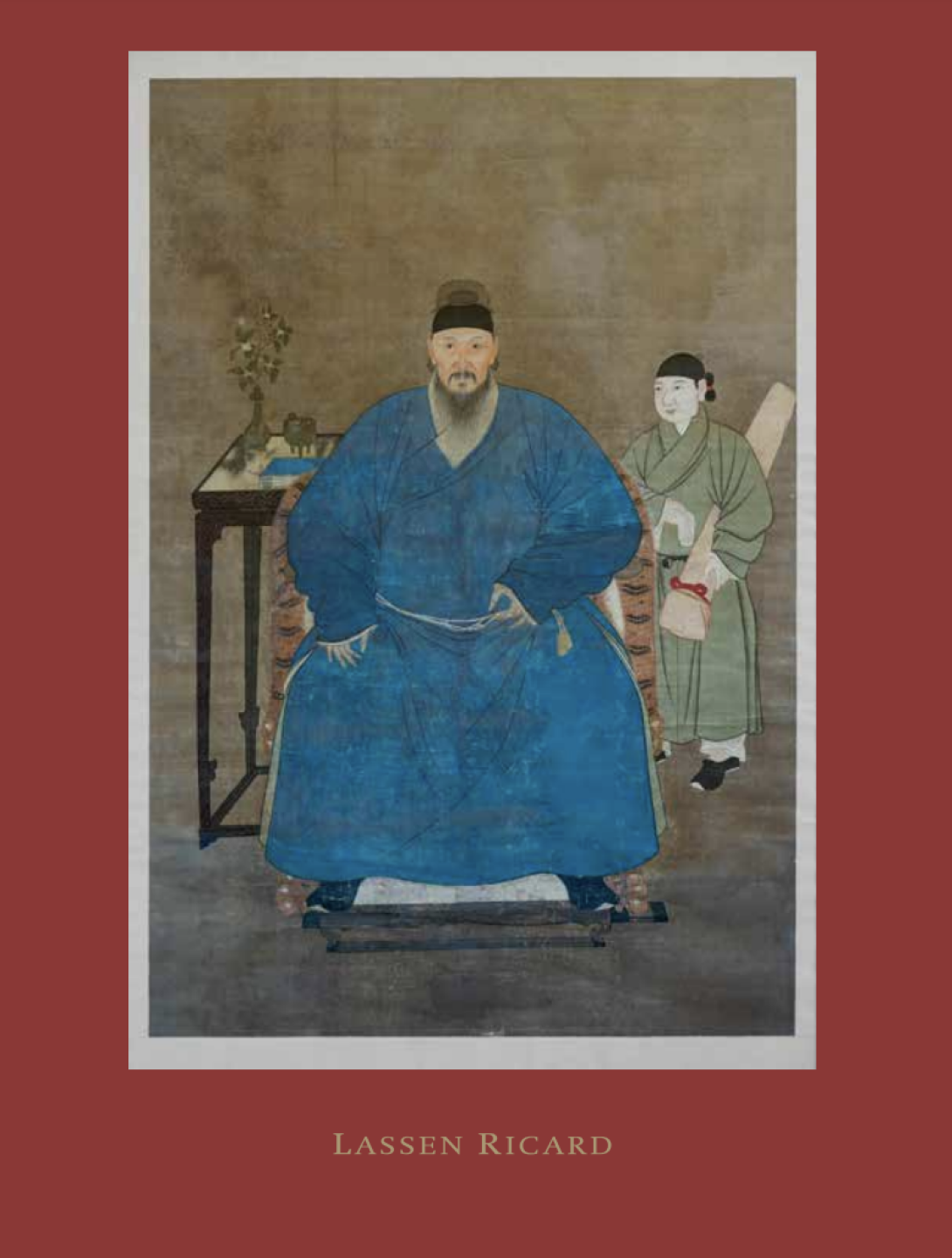

ENTERING THE YEAR OF THE OX 2021

There hangs a Chinese artwork on the far wall of Lassen Ricard’s conference room. It is there to remind us of a world bigger and richer and more wondrous than that just outside the window. Who are we? According to Chinese culture we are rats, dogs and oxen, all depending on the year we were born – as was determined by the fantastic zodiac race. The Jade Emperor decided to host all the animals in the world. The first twelve that finished the race would be accepted into the zodiac wheel. At the time, the rat and the cat were dear friends. They decided to jump onto the ox and cross the river together. Suddenly, in the middle of the river, the rat moved higher up the ox – and pushed the cat into the water. As the ox approached the finishing line, the rat leapt down ahead of the ox and came first. The ox was too good-natured to be bothered about it. But the cat never reached the finishing line – and has hated both water and rats ever since. The twelve animals admitted into the zodiac were: the rat, the ox, the tiger, the rabbit, the dragon, the snake, the horse, the goat, the monkey, the rooster, the dog and the pig. They each represent a year in the Chinese calendar’s twelve year cycle. In Chinese culture, humans are bound with nature as a single entity. And we are assigned a particular animal depending on the lunar year in which we are born.

The Chinese calendar is a lunisolar calendar, which the Chinese still use to mark traditional holidays, like for example, Chinese New Year. The zodiac chart was established 3000 years ago during the Xia dynasty and the next new year commences on Friday the 12th of February – and will be… the Year of the Ox. So if you were born in 1949, 1961, 1973, 1985, 1997 or 2009, or if you are born in 2021, you have the same characteristics as the Ox. These are sensible people, serious, level-headed and steady. They proceed in accordance with their own ideas and abilities, unperturbed by others. Before they act, they take care to think things through. They distinguish easily right from wrong and they keep to the rules. They are gentle and kind, idealistic and ambitious and they take great interest in their family and their work. They have a rich emotional life in which love and hate are separate, and they are successful. Who wouldn’t want to be an ox? But each animal has its own qualities and characteristics – and each will have its turn in the Chinese zodiac. And the cat? The cat goes its own way.

___

Text: Knud Romer

Photo: Jens Markus Lindhe

MERRY CHRISTMAS AND HAPPY NEW YEAR

2019

Christmas card 2019

LIFE IN ALLEGORY

Look up at the sky a frost clear night. You disappear in a myriad of stars. But the moment we trace them into figures, we impose an order, and they make sense: a gallery of stars telling their stories, mythologies.

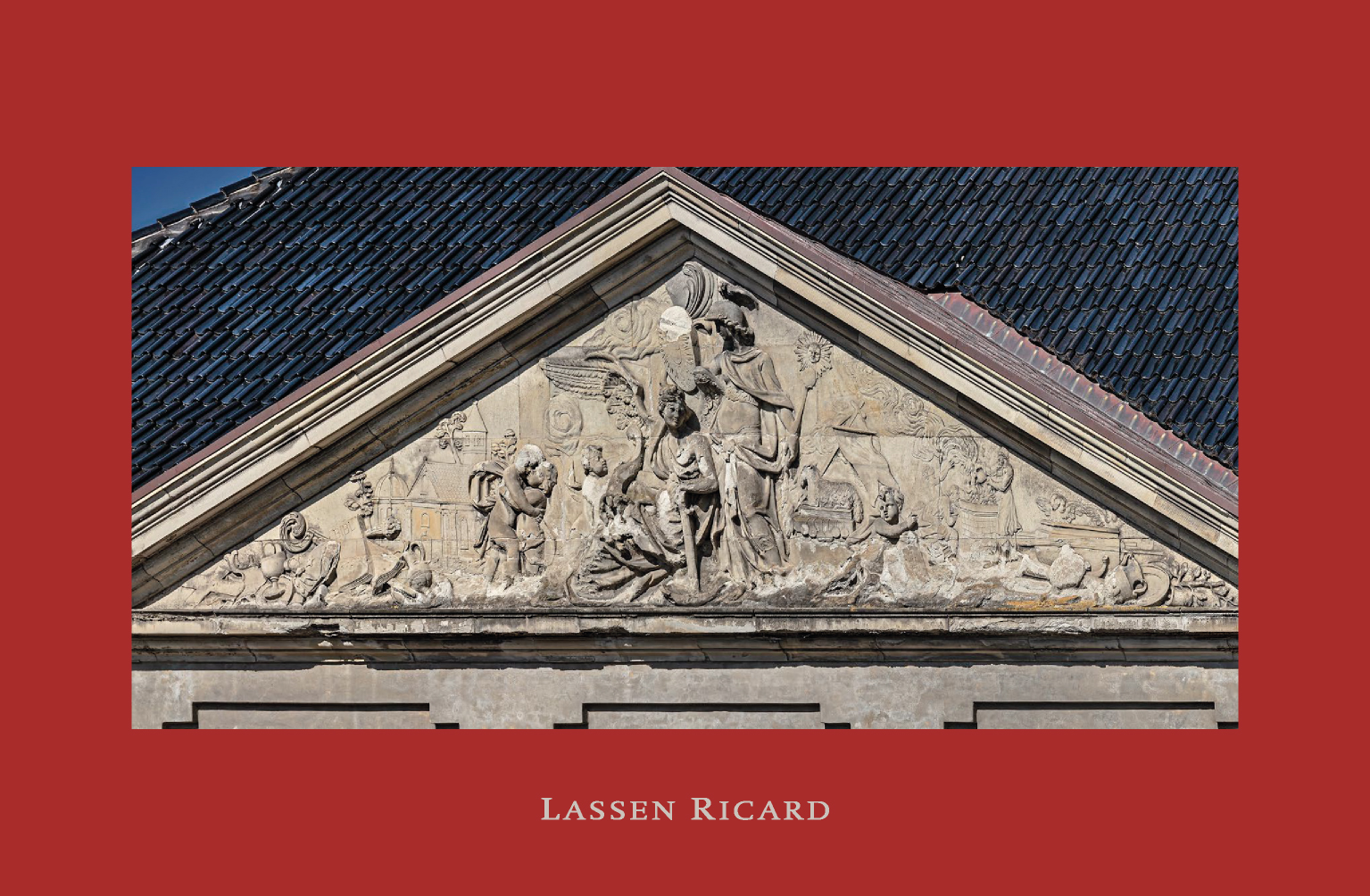

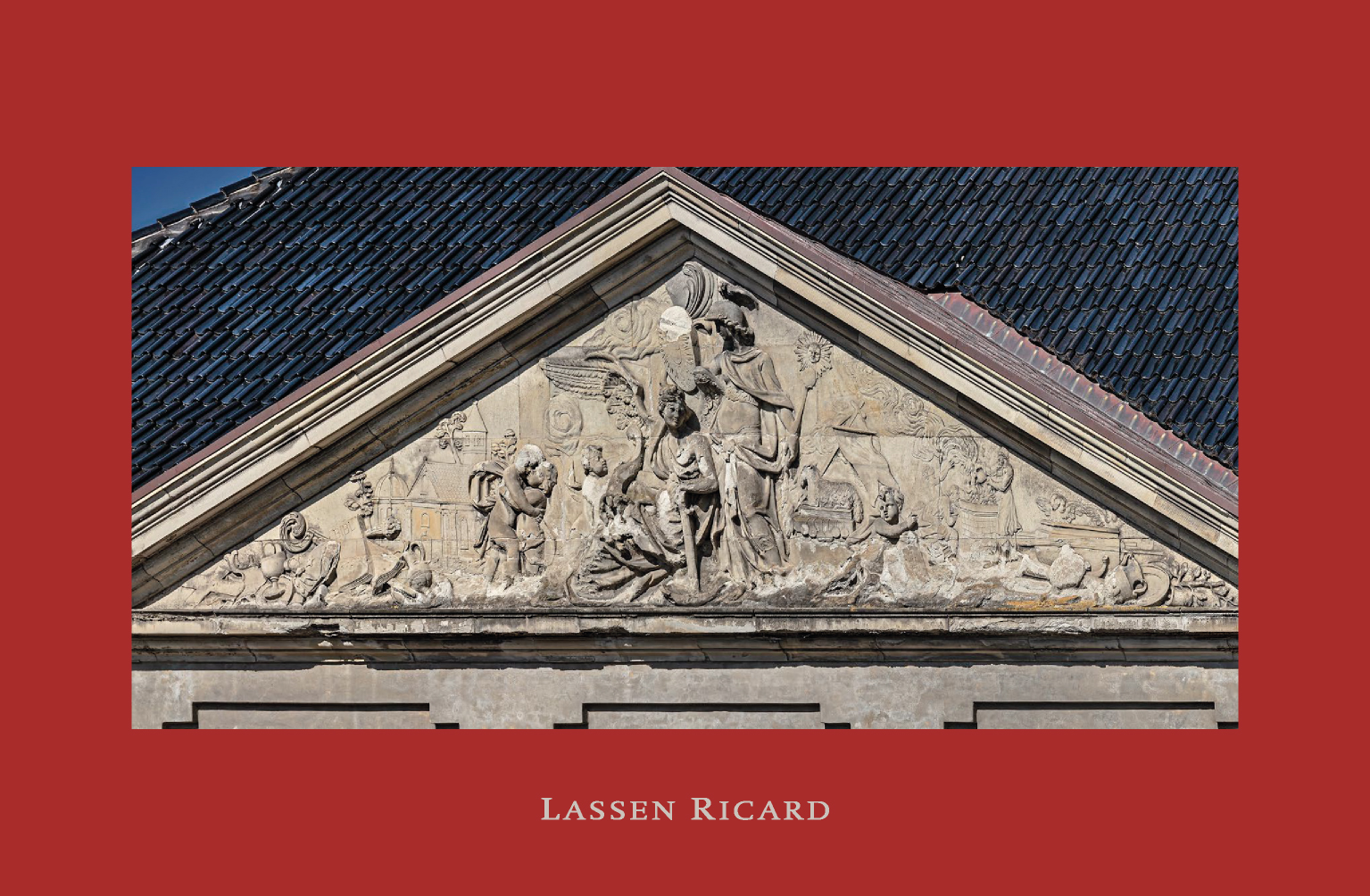

Where Lassen Ricard has its domicile at the old Frederik’s Hospital there is a gable relief that is as the starlit sky. We see a woman with wings and flames in her hair, another with a dove on her helmet. A lamb on a book. Naked children – two rotund cherubs in an embrace – a crosier, mitre, chalice, alter piece and jug, all spread around them, as if a ruin mound, whittled by time.

It is an allegory. And if you know your art history, you may be reminded of Albrecht Dürer: Melancholia I.

Here a wingéd woman sits in grave contemplation, her head resting on her palm, staring at a landscape that is scattered with geometric and alchemic symbols, and a ladder leads out of the image of melancholy amidst catastrophe: the loss of meaning.

The history is gone, and all that remains is the knowledge of the insignificance of mere things; we are but things amidst things, which have no meaning: an obscure relief on a gable end.

This is, and has always been, the order of things – but the shattering of illusions need not be tragic, for man is granted his rightful place in the universe instead.

It is not the end – but the beginning – of the story, for we are the source of meaning; we establish and live our lives in the cheerful knowledge of an infinite, creative impulse, in allegory.

In 1840 an early source ascribes the composition on the gable end on Amaliegade as a depiction of Wisdom, Faith, Knowledge and Humanity. This brings a gospel for Christmas, a goal to reach for.

Merry Christmas!

___

Text: Knud Romer

Photo: Jens Markus Lindhe

MERRY CHRISTMAS AND HAPPY NEW YEAR

2018

Christmas card 2018

Baroque

That’s Baroque! This expression can be interpreted as criticism, as praise and as a term denoting an architectural style – the style in which Lassen Ricard’s headquarters (part of the former Royal Frederik’s Hospital) is built. The Baroque style was sweeping: it could be dramatic, subdued, full of riotous colour, brilliantly illusionistic and breathtakingly monumental. It lasted from the mid-16th century to the end of the 18th century, spreading geographically throughout Europe and beyond to Latin America. Its legacy includes a wealth of expressive paintings, vibrant sculptures, dazzling buildings and elegant gardens replete with avenues of trees and reflecting pools. The enduring popularity of the Baroque lies in its appeal to both our intellect and our emotions – it sparked intuitive understanding and struck a universal chord. Although its flamboyance occasionally verged on the preposterous, it was never trivial. This made the style an exceptionally good tool for those in power looking to project their might and the reach of their authority. During the Baroque era, art was generally acknowledged as the visible manifestation of one’s prowess.

A person who could commission magnificent art must necessarily possess similar qualities in all other fields. This perception was used to great advantage by such figures as Catholic church leaders and Louis XIV of France, as well as by Frederik V of Denmark through the building that now houses the Lassen Ricard headquarters. Impressive and instantly accessible, Baroque art played an important role in the politics of the day.

___

Text: Ulla Kjær, PhD, curator and senior researcher at the National Museum of Denmark

Photo: Jens Markus Lindhe

Merry Christmas

and Happy New Year

2017

Christmas card 2017

Photo: Jens Markus Lindhe

2016

Christmas card 2016

THE CHRISTMAS ANGEL ABOVE AMALIEGADE 31

The bird table is crowded. You can draw heart shapes in your breath on the cold window pane. Before you know it Christmas comes around, and suddenly snow is falling. Christmas cookies are made in all shapes and sizes; gingerbread men and gingerbread ladies, shooting stars. There’s a lovely smell of cinnamon, and angels are twisting and tinkling in candlesticks. Daddy has kissed mommy in her Santa hat.

Christmas is one of our most beautiful inventions, and it’s found nowhere else in the universe. For we live in a world that we have shaped ourselves. The sky above us is our own, created from our notion of who we are, and where we are, and what is happening – mythology, religion, history, science: Stories.

Maybe that is why it feels as if someone up there is keeping an eye on us, and when we place the star on top of the tree, it’s in celebration of the child. Infant Jesus lay in a manger – that’s our first experience in the cradle – and mother and father looked down. It was the safest place of all, a nest where you belonged. They looked after you and made the world small. It was yours.

Life is a gift wrapped in unending paper. You can keep unwrapping and never reach the end. We are a mystery to ourselves, and on Christmas Eve what is best in you – your sweet tooth, your painful longing, and everything that you could wish for – becomes an angel.

You cannot see it. But it sees you and twinkles at you from Paradise.

___

Text: Knud Romer

MERRY CHRISTMAS AND HAPPY NEW YEAR

2015

Christmas card 2015

THE STAR OVER FREDERIKSSTADEN

When night falls and Christmas draws near, a star shines over Frederiksstaden in Copenhagen – you can see it right there above the palace at Amaliegade 31. That is Ilia Fibiger. She lived true to ideals that went beyond herself, and she did what was inconceivable for a middle-class woman in 1854: She moved in and became a foster mother at Frederiks Hospital.

At that time this was the final destination; a place where you did not go to be cured, but to die. She looked after the night nurses and the patients – the poor and outcast – and improved the hospital conditions with self-sacrifice bordering on self-destruction.

Ilia Fibiger became the first professional nurse in Denmark, and the hospital service developed into what it is today. She was our Florence Nightingale and lighted a candle in the dark that to this day spreads the true Christmas tidings:

That life is a gift, and the meaning of life is to give like the star that shines over Frederiksstaden.

___

Text: Knud Romer

Front page photo: Jens Markus Lindhe

MERRY CHRISTMAS

AND HAPPY NEW YEAR

2014

Christmas card 2014

Two children stand between the pavilion buildings facing Amaliegade, gazing in at the Royal Frederik’s Hospital. Fortunately for them, they look healthy and happy, because had they been sick, the hospital would not have been the place for them. The Royal Frederik’s Hospital was inaugurated in 1757 as the first proper hospital in Denmark. This distinctive building in the new urban district of Frederiksstaden was constructed to celebrate the 300th jubilee of the Oldenburg dynasty. For this reason, the hospital was planned to accommodate 300 patients, and its mission was to cure ablebodied people. Admission to the hospital was denied to children under seven, the chronically ill and the infirm.

What did ailing citizens do before the hospital was built? Medical education of the time was well-established, but erratic in quality. Only a handful of doctors practiced medicine, and their fees had to be paid out of patients’ own pockets. In reality, this meant that only the wealthy had access to medical care, and those in need of medical attention were both examined and treated at home. Thus, most people had to make do with the help of family and friends or so-called wise men and women.

Disease was generally believed to result from an imbalance between the four body humours: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. The treatments doctors used to redress the balance included blood-letting; cupping; the application of leeches, hot poultices or plasters containing Spanish flies; castor oil or enemas; and various emetics to induce vomiting.

Many doctors believed the body should overcome disease on its own and that any treatment should merely support the natural healing process. Although unaware of this philosophy, many patients were undoubtedly grateful for the approach. The list of remedies suggested by good friends and wise men and women was long and imaginative. Submitting one’s body to such dubious cures was not always fun and at times even fatal.

Initially the Royal Frederik’s Hospital offered no new or better treatment, but its patients were cared for and avoided the most fanciful remedies. With patients admitted to hospital, doctors could follow them at close hand, thus gaining new knowledge and experience regarding the course of diseases and the results of treatment. The hospital laid the foundation for the clinical development that was decisive to the evolution of our modern healthcare system.

To the left of the children in the photograph is the Baroque mansion that was once part of the Royal Frederik’s Hospital and now houses the headquarters of Lassen Ricard.

___

Text: Ion Meyer, Deputy Curator, Collections Manager, Medical Museion

Photo: THE PICTURE ARCHIVES OF THE MUSEUM OF COPENHAGEN

MERRY CHRISTMAS AND HAPPY NEW YEAR

2013

Christmas card 2013

Søren Kierkegaard 200 years

TO BE PRESENT TO YOURSELF

This year marks two hundred years since Søren Kierkegaard was born in Copenhagen, a city he loved – and at times hated. His life ended at the age of forty-two at Frederik’s Hospital, which was located at the same site in Amaliegade where Lassen Ricard is housed today. Yet during his short life, Copenhagen’s philosopher managed to produce an authorship that has altered thinking throughout the world. Many of his writings show signs that he was an urban thinker, a modern man who felt at home in the city.

But he also loved to get out to the countryside and experience nature. This comes to expression in many of his edifying discourses in which one of the most complicated modern thinkers celebrates the simple, immediate joy of being alive, of sensing one’s own existence right now, or as he calls it, of “being present to yourself”:

“You should learn from the lily and the bird, learn to be present to yourself. Think, that you were born, that you exist, now; that you, ‘this day,’ have what you need to exist; that you can see, that you can hear, that you can smell, that you can taste, that you can feel; that the sun shines for you – and for your sake; and that when it wearies, the moon begins to shine and the stars are lit; that winter comes, and all nature disguises itself, plays the role of foreigner – and does so to enchant you; that spring comes. And should all this be nothing to rejoice over? If this is not something to rejoice over, then nothing is.”

___

Text: Brian Söderquist, PhD in theology

Photo: Jens Markus Lindhe

MERRY CHRISTMAS AND HAPPY NEW YEAR

2012

Christmas card 2012

The passers-by

Time goes on and on, and we move with it without a thought until something brings us up short: the imposing mansion at 31 Amaliegade. So it is with historic buildings. They are bound to the place, punctuating time and space and transforming everything around them. We are reminded of the fleeting nature of our existence and mortality compared with the buildings, which stood there before us and will endure after we are gone, and suddenly a whirligig of dry leaves blows through the empty streets.

Marcus Aurelius is quoted as saying that time is a river of events, a strong current. It is here for a moment, then it is gone, turned into something new and different. Renewal and change moving ever forward. Linear time: history as we perceive it today.

But once a year we return to a past when time stands still and everything comes full circle. Where what is important is not change, but traditions and the past. A cyclical, ritual time governed by repetition and identity, the same thing over and over again: Christmas.

For a brief moment we are controlled by something greater and more universal than ourselves, and we become part of the same history, all of us – young and old, the living and the dead – we are the same as those who have gone before us and those who will come after. It has always been thus.

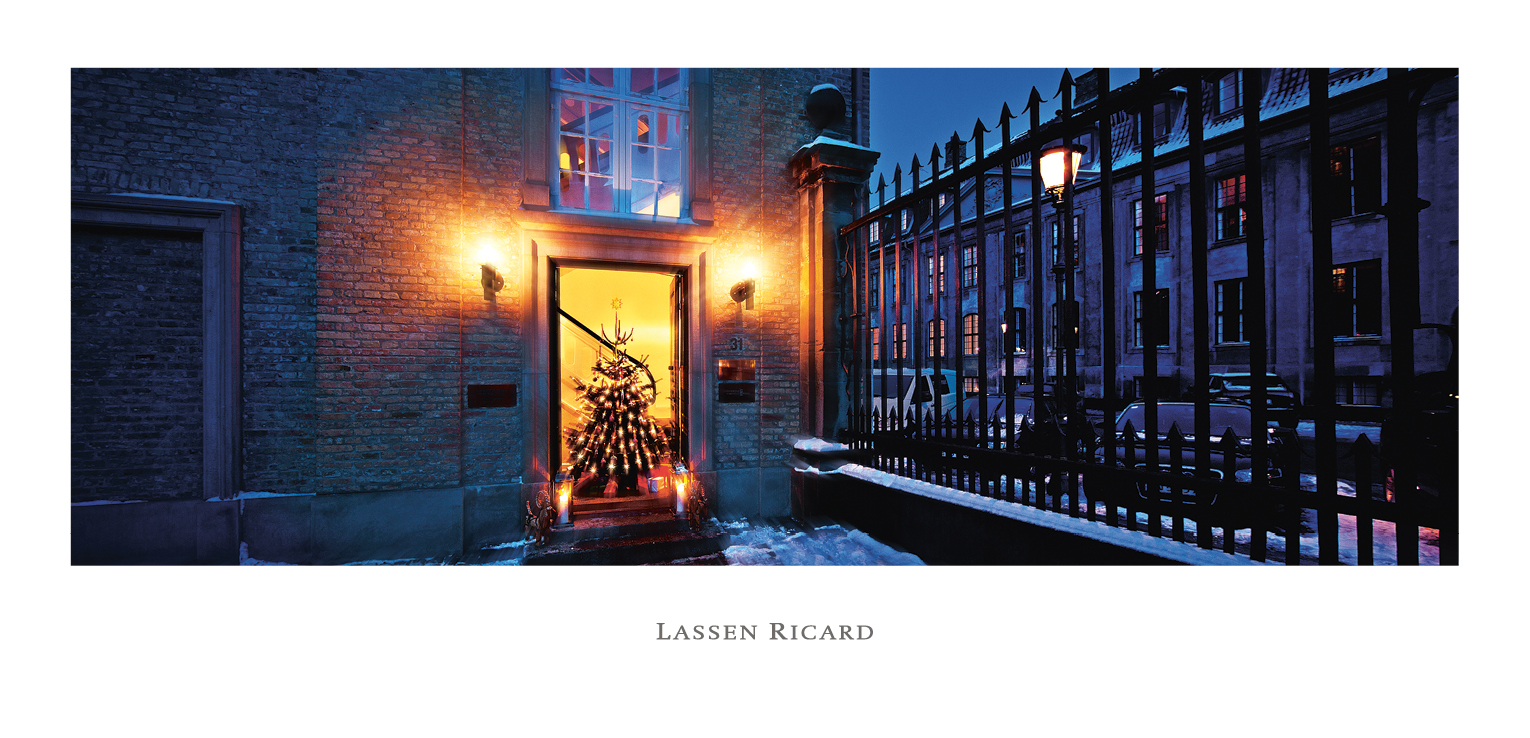

The mansion at 31 Amaliegade will endure, and we are the passers-by who enter history through the door to the building that once was Frederik’s Hospital. The Christmas tree stands in the courtyard outside marking time and the season – the evergreen tree that withers – this is you and me, now and for all time.

___

Text: Knud Romer

Photo: MUSEUM OF COPENHAGEN

MERRY CHRISTMAS AND HAPPY NEW YEAR

2011

Christmas card 2011

Lassen Ricard 2011

Every December visitors to Lassen Ricard’s headquarters in Amaliegade are greeted by the sight of a Christmas tree from one of the law company’s clients, the Mattrup manor estate in Jutland. The manor house, whose oldest wing dates back to the 14th century, has been the property of the Westenholz family since 1853, when the 38-year-old Copenhagen merchant Regnar Westenholz decided to become an estate owner near Horsens.

Today Mattrup’s fame extends beyond Denmark’s borders thanks to the world-renowned 20th-century Danish author, Karen Blixen, whose mother, Ingeborg, was born there. After the premature death of Blixen’s father, Wilhelm Dinesen, life at Rungstedlund was marked by the solid moral values of her mother’s family. In the author’s mind, Mattrup came to represent not only the people she had loved as a child, but also the type of person she vowed never to become as an adult: a bourgeois zealot.

Nevertheless, as major shareholders in Karen Coffee Limited, it was the Westenholz family who financed the author’s life dream for 18 years. Far from Denmark’s shores on a coffee farm outside Nairobi, Blixen lived among British aristocrats and the natives of the Masai Mara.

Karen Blixen’s husband at the time, Baron Bror Blixen, had bought the farm in 1913, using his in-laws’ family legacy to pay for it. However, the farm’s altitude and location proved completely unsuitable for profitable coffee cultivation. Karen Blixen’s uncle, Aage Westenholz, who later became the board chairman and was familiar with running plantations from his ownership of United Plantations in Siam, had already foreseen this risk before Bror Blixen purchased the property.

It was the largess of Aage Westenholz and his sister that allowed the rebellious Blixen spirit full rein, regardless of the cost and the dwindling prospect of ever turning the investment into income. However, the end of the story is that three years after the bankruptcy and forced sale of the farm in 1931, a genuine English-speaking author of unique artistic calibre emerged set for a career that would have been inconceivable without the 18 harsh years of experience gained in British East Africa. An accomplishment worth decorating a Christmas tree for.

___

Text: Poul Behrendt, Associate Professor Emeritus, University of Copenhagen

Photo: Ted Fahn

SEASON’S GREETINGS AND BEST WISHES FOR THE NEW YEAR

2010

Christmas card 2010

Lassen Ricard’s domicile is not merely a Baroque mansion. It is also a personal testimony to Royal Architect Lauritz de Thurah (1706-1759). One cannot tell Thurah’s story without mentioning the bitter rivalry that existed between him and architect Nicolai Eigtved (1701-1754). In the 1730-40s, Thurah favoured the Germanic Late Baroque style that distinguished the royal building projects of the time. However, when a new king ascended the throne in 1746, Thurah was supplanted by Eigtved, whose French Rococo style – a style alien to Thurah – was more to the taste of the leaders then in power. Eigtved was assigned the prestigious task of drawing up a plan for Frederiksstaden, a new city quarter intended to reflect glory on the absolute monarch. In the meantime, Thurah had to settle for repairing and rebuilding the royal country residences in the provinces; out in the cold, far away from the life of the court in Copenhagen. Thurah had been thoroughly demoted, and he bore considerable resentment. The rivalry between the two court architects grew into artistic and personal hostility.

However, Eigtved died while Frederik’s Hospital in Frederiksstaden was being built, and Thurah was recalled to Copenhagen to complete the Hospital. It is tempting to read the changes Thurah made to Eigtved’s building (now The Danish Museum of Art & Design) as his revenge, in particular his four pavilions facing Bredgade and Amaliegade (one of which is now Lassen Ricard’s domicile).

Purists would probably claim that Thurah’s large pavilions almost dwarf Eigtved’s delicate main building. Others might point out that Thurah’s additions lend the buildings a grandeur that transforms the hospital into a princely castle – an achievement of which he himself was fiercely proud. A little pomp is good for sick patients too. Thurah’s solid Baroque style acts as a foil for Eigtved’s light, well-ordered Rococo vision. Nothing is complete in itself. The two enemies’ works both contest and complement each other. Two equal, yet opposing masters. A mirror of life itself, full of delightful contrasts.

___

Text: Ulrik Langen (PhD), historian and author

Photo: Jens Markus Lindhe

SEASON’S GREETINGS AND BEST WISHES FOR THE NEW YEAR

2009

Christmas card 2009

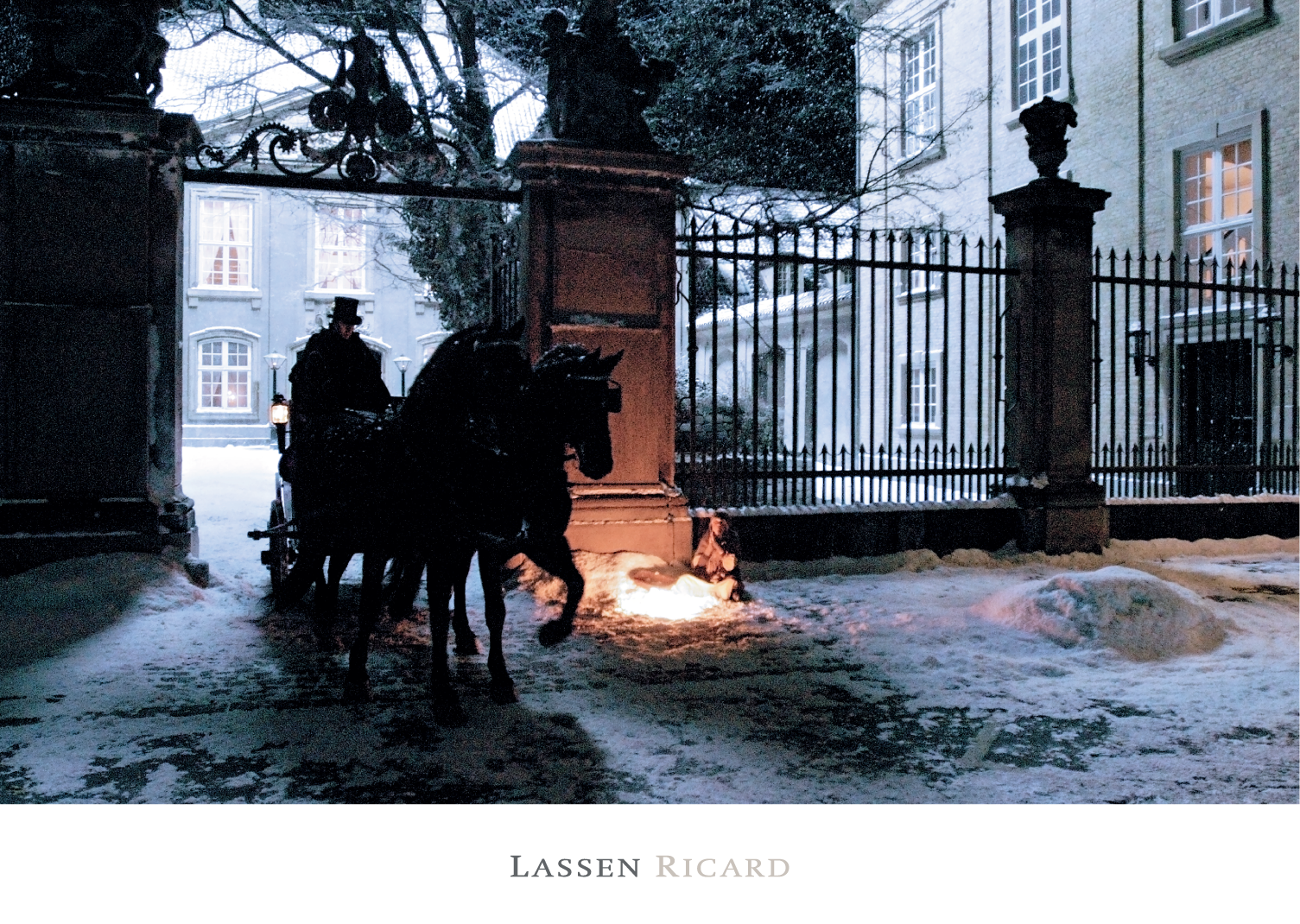

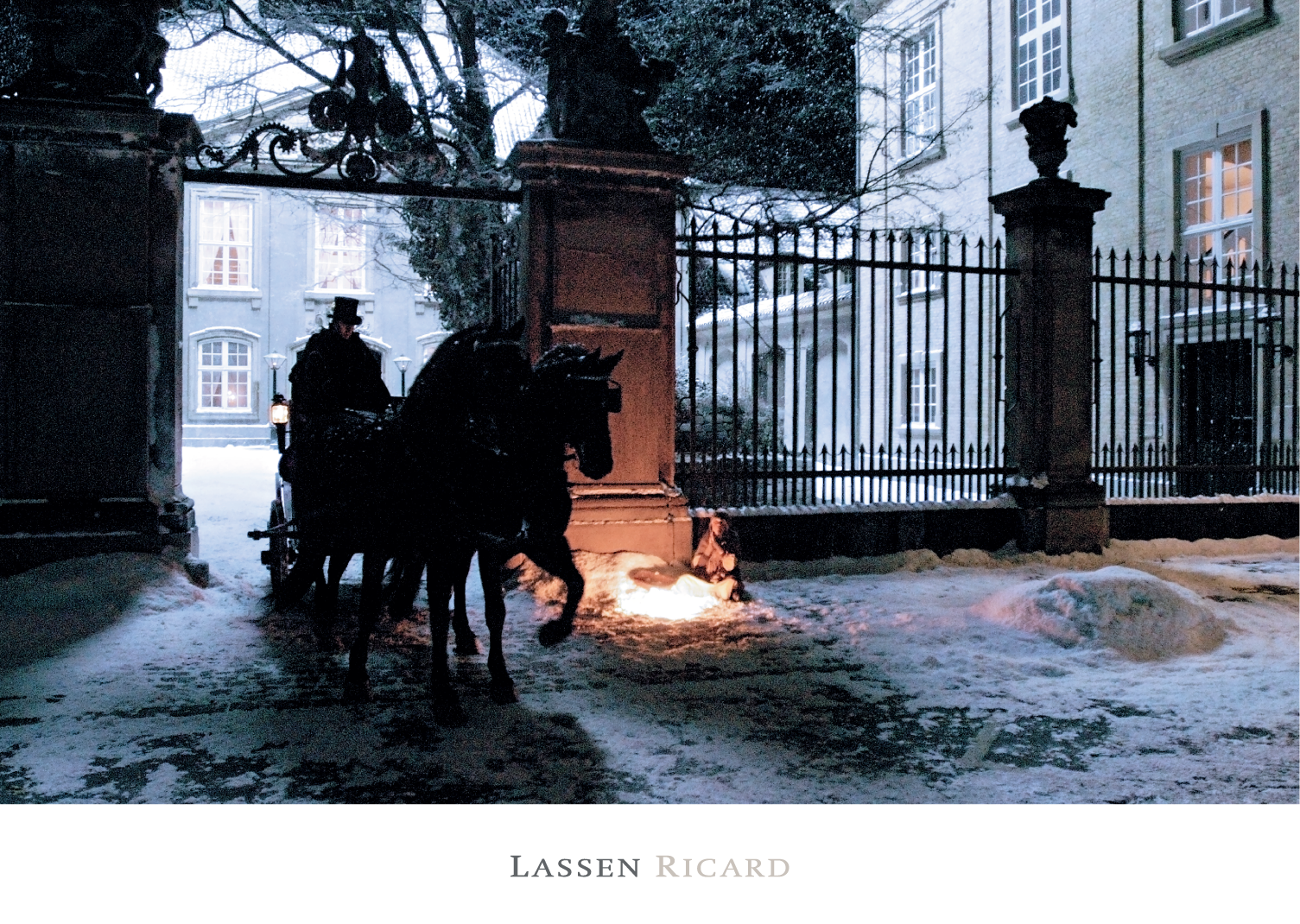

The picture of Lassen Ricard’s head office is taken from the drama series “Harry & Charles”, to be broadcast at Christmas 2009 by the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation on national television. Cable TV viewers in Denmark will also be able to follow the series, which chronicles how Danish Prince Carl and his wife Princess Maud became Norway’s first king and queen since the Middle Ages.

After 400 years of union, Denmark had to relinquish Norway to Sweden in 1814 after being on the losing side in the Napoleonic wars. Norway and Sweden were now united under one monarch.

On 7 June 1905, the Norwegian parliament decided to dissolve the union, and Swedish King Oscar II, who was also the king of Norway, was forced to abdicate the Norwegian throne. The Norwegian parliament offered the vacant throne to 33-year-old Prince Carl, the second-eldest son of the Danish crown prince. It would be an advantage to have a Scandinavian king whose ancestors could be traced back to mediaeval times and who understood the Norwegian language and culture. The fact that he had already produced an heir, two-year-old Alexander, was seen as a further advantage.

Prince Carl made his acceptance contingent on the outcome of a Norwegian referendum, and when the referendum returned an overwhelming majority in favour of the monarchy, he agreed.

Prince Carl took the name Haakon after the Norwegian kings of the Middle Ages and gave his son the name Olav. The coronation of King Haakon VII and Queen Maud took place on 22 June 1906 in Trondheim. Prince Carl thus succeeded in becoming king before both his father, later King Frederik VIII of Denmark, and his elder brother, who became King Christian X of Denmark. Queen Maud died in 1938 and King Haakon VII in 1957.

___

Photo: Lars Vestergaard

SEASON’S GREETINGS AND BEST WISHES FOR THE NEW YEAR

2007

Christmas card 2007

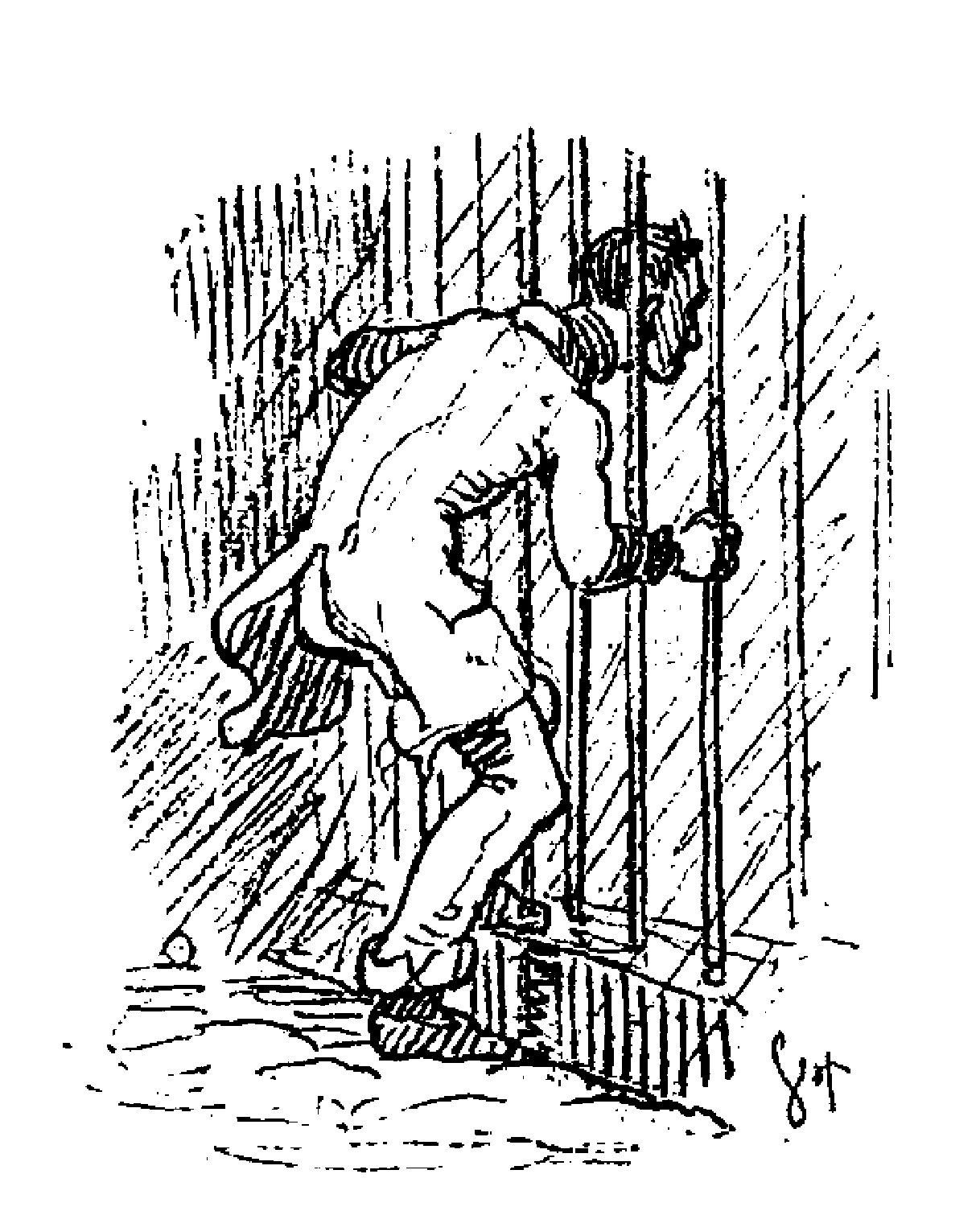

H.C. Andersen has described the high railing of heavy iron bars in front of Lassen Ricard’s domicile - the former Frederik’s Hospital - in The Galoshes of Fortune:

A Great Moment

Everyone in Copenhagen knows what the entrance to Frederic’s Hospital looks like, but as some of the people who read this story may not have been to Copenhagen, we must describe the building-briefly. The hospital is fenced off from the street by a rather high railing of heavy iron bars, which are spaced far enough apart - at least so the story goes - for very thin internes to squeeze between them and pay little visits to the world outside. The part of the body they had most difficulty in squeezing through was the head. In this, as often happens in the world, small heads were the most successful.

___

Drawing Vilhelm Pedersen 1894

Copyright H.C. Andersens Hus / Odense Bys Museer

Cover photo: Jens Markus Lindhe

SEASON’S GREETINGS AND

BEST WISHES FOR THE NEW YEAR

2006

Christmas card 2006

Season's Greetings and

best wishes for the New Year

Photo: Jens Markus Lindhe

2005

Christmas card 2005

With the domicile of Lassen Ricard as setting our Christmas card shows a scene from the TV series “Unge Andersen” (“Young Andersen”). The TV series, which won an Emmy in the autumn of 2005, is produced to mark H. C. Andersen’s 200th birthday 2 April 2005.

She hurried across the street to avoid two carriages rattling past at great speed...

-The true story of “The Little Match Girl”

By all accounts, it’s absolutely true: at some time or other, Chinese schoolchildren – all 200 million of them – read a work by Hans Christian Andersen as part of their education. China’s great and mighty Chairman Mao purportedly ordered the reading of one or more of Andersen’s fairy tales, a decree that has indubitably made the entire Chinese nation familiar with “The Little Match Girl”, and on occasion even some of the poet’s other stories.

And why did he single out "The Little Match Girl"? Because Mao, if indeed it was he, apparently found this story eminently suited to illustrating the hardships inherent in the Western capitalist system.

However, it would take a vigilant reader to detect any criticism of ‘capitalism’ in Andersen’s story, as the political ideology was barely in evidence in Denmark at the time the story was written. It was penned in 1845, midway through the last decade of absolutism, which had held sway in the country for almost 200 years.

In its time, the story – for a fairy tale it is not – acted as a social eye-opener, its impact paralleling that of works like "Oliver Twist" by Charles Dickens (1838). And oddly enough, professional readers scoff at Dickens’ novel and Andersen’s story, both of which they find nauseatingly sentimental. A website about "Oliver Twist" claims Dickens would have been better off never writing the novel. A curious point of view given the many film versions of Dickens’ most famous novel, also turned into a musical and adapted to various other media. Andersen’s equally famous story shares the same fate, with numerous films and an animated feature to its credit. However, the truth of the matter is that fame and popularity are no guarantee that pundits will consider a work to have merit.

In Denmark, "The Little Match Girl" is often re-told at Christmas-time, although it is not a Christmas story at all. It takes place on New Year’s Eve and ends on the morning of New Year’s Day. The story starts with these words:

It was bitterly cold. Snow was falling and darkness was encroaching. It was also the last evening of the year, New Year’s Eve.

And it ends like this:

But in the cold morning light sat the little girl, in the corner between the houses, with rosy cheeks and a smile on her lips – frozen to death on the last night of the old year. New Year’s Day broke on the little body still grasping the matchsticks, of which one bundle was almost burnt to the ends. She wanted to warm herself, people said. No-one knew what beauty she had seen, in what a halo she had entered with her grandmother into the glories of the New Year!

A series of luminous visions precedes this final sequence with the death of the little girl, visions conjured up by the light and fleeting warmth she creates by striking some of the matches she never managed to sell. Logically speaking, a chain of dream images. One vision is of a huge Christmas tree with thousands of candles on its branches. The Christmas tree notwithstanding, the story remains a New Year story, a fact crucial to its interpretation. If we lose sight of this element, we lose the gist of the story, as has an American film animation in which the little girl finds herself frolicking with cherubs and being showered with Christmas presents.

Yet, rather than dwelling on the end of the story, perhaps we should return to the very beginning and find out how it all started, which is quite a story in its own right.

On 31 October 1845, Hans Christian Andersen left Copenhagen to travel around Europe. Passing through Germany, Austria, Italy, Switzerland and returning via Germany, the round trip ended up lasting almost a year, with Andersen not arriving back in Denmark until 14 October 1846.

On the outbound journey, he spent 10 days from 12-22 November as the guest of the Duke and Duchess of Augustenborg at their hunting retreat, Gråsten, or Gravensteen, as it was then called.

During his stay, on 18 November, he received a letter from Copenhagen from a xylographer by the name of Flinch. Flinch, who had established his own ‘xylographic institute’ in 1840, started publishing an illustrated Almanak eller Huuskalender [Almanac or Household Calendar], for which he had various artists (and ostensible artists) provide illustrations.

In his letter, Flinch enclosed three almanac illustrations used earlier in a different context, asking Andersen whether he might write a tale to accompany one of them.

One depicted a little, shabbily dressed girl, apparently barefoot, her back half-turned to the onlooker, holding a bag in one hand and a bundle of matches outstretched in the other. A beggar girl in other words. At the time, begging was forbidden, but one way of evading the prohibition was under the guise of selling matches.

The picture by artist J.Th. Lundbye had previously been published in an article warning the bourgeoisie against giving money to beggar children. ‘Do good when you give!’ was the title of the work, whose point was that submitting to the children’s appeals would only make bad worse. On the contrary, would-be givers should snap their eyes and ears, and especially their purses, shut in the hope that this would force the children’s lazy parents to find work and send their children to learn at school instead of running around begging, a pastime that only led to the children’s own ruin. Thanks to the misguided generosity of their so-called benefactors, the children would not become ‘decent, upright folk’, but rather grow up in ‘sloth, ignorance and sin’.

A litany echoed through the ages, right up to the present time!

We do not know whether Andersen himself had heard of this moral caution, or whether he only saw the pictures.

Lundbye’s portrayal of the little match girl captured Andersen’s imagination immediately, and the poet penned his story about the little beggar girl and her fate on the same day he received the letter. Perhaps he did so in protest against the social callousness of the period; perhaps the picture reminded him of something his mother once told him.

The anecdote comes not from Andersen himself, but from his younger friend Nicolai Bøgh, who referred to it in a book from 1905. Although unverified, story has it that Andersen’s mother was sent out as a child to beg. After sitting crying under a bridge across Odense river, she returned home empty-handed, and her mother scolded her for being such a lazy girl.

Whatever it was that prompted Andersen to choose the picture of the beggar girl with the matchsticks, he dashed off a draft, made a fair copy the next day, 19 November, and dispatched it by letter. And anyone who thinks Hans Christian Andersen wanted to repress his humble beginnings as he climbed the social ladder would do well to remember that he actually wrote "The Little Match Girl" while staying at Gråsten Palace!

In a corner between two houses, one of which projected a little beyond the other, she curled up, drawing her legs beneath her. She was colder than ever, but dared not return home because she had sold no matches, nor earned a single penny, and her father would surely beat her. Besides, it was cold at home, for they had nothing over them but a roof through which the wind whistled even though they had stuffed the biggest cracks with rags and straw. Her little hands were almost stiff with cold.

Anyone accusing Andersen of sentimentality should take pause to consider the story’s purpose. Andersen takes pains to identify closely with the little girl, giving contemporary readers tempted to follow the philanthropic advice and refuse to donate anything to beggar children a sense of their destitution and thus arousing feelings of compassion.

Call Andersen’s and Dickens’ approach sentimental if you like, but some hard hearts definitely had to be softened before their owners could be made to understand the fate of these children.

The remarkable thing about Andersen’s story is that, despite its social premise and socially related message, it has other, deeper reverberations that strike far into the heart of Andersen’s own philosophy of life.

The story has an ‘outside’ dimension, an outside where darkness, cold and hunger reign. In contrast to this, we experience light that grows gradually stronger with every new match the girl strikes. The light from the matches penetrates the cold hard wall that she leans against and that bars her from all the life-giving activities on the other side. Finally, the light becomes all-embracing, manifested as a huge Christmas tree with thousands of candles enfolding her. When the Christmas tree with its candles is extinguished, a star arcs its way across the sky.

Granted, a shooting star is about wishes coming true, but here it assumes a different meaning. The girl’s grandmother has taught her that a shooting star means someone is about to die. It foreshadows the girl’s own death, but the portent is a shooting star, a heavenly symbol that also signifies fulfilment. Death and destruction, fulfilment and climax in one!

The next time the little girl strikes a match, her grandmother does appear. Strangely, the girl realises the old woman is an illusion and that the image will disappear as soon as the matches go out. Nonetheless she begs her grandmother to take her along! This is the crux of the story: vision is stronger than reality, light is stronger than dark. The little girl’s death in darkness, cold, hunger and misery represents a maximum of light, intensity, closeness and fulfilment. New Year’s Eve is succeeded by New Year’s morning; one thing ends and something new can now begin.

This theme recurs time and again in works by Hans Christian Andersen: the paradoxical juxtaposition of destruction and creation, dark and light, death and birth. We need go no further than one of his earliest and also best-known poems, ‘The Dying Child’, written in 1826 while he was still attending school in Elsinore.

It is dark outside, a winter gale is raging, and a mother weeps for her dying child. The child, however, sees a light ever intensifying until the moment the angel kisses the child, and it dies. This death is a pinnacle of light and sublimity!

We find similar instances throughout Andersen’s oeuvre. Another poem of his youth, ‘The Moment of Death’ (1829), deals with the same subject, as do his lyrical, musical Christmas tale ‘The Last Dream of the Old Oak Tree’ (1858) and the ending of ‘A Story from the Sand Dunes’ (1859).

In short, Andersen’s all-consuming focus in "The Little Match Girl" differs completely from that which (allegedly) prompted Chairman Mao to make the story compulsory reading for Chinese schoolchildren. It is also a far cry from the syrupy sweetness that causes modern-day readers to balk at the story.

The same mystical, paradoxical view of life’s continuation into and after death underlies the lines of verse etched on Hans Christian Andersen’s gravestone in the Assistens cemetery in Copenhagen:

God created in His image the human soul,

Forever true, forever whole.

From our earthly life eternity springs,

Our body dies, our soul immortal sings!

_____

Text: Johan de Mylius, born 1944, PhD, senior associate professor and head of the Hans Christian Andersen Center at the University of Southern Denmark since 1988. Johan de Mylius has authored numerous books and articles on Danish literary history, including on authors such as Thomas Kingo, Johannes Ewald, Søren Kierkegaard, Vilhelm Topsøe, Henrik Pontoppidan and Karen Blixen. He has also written about 18th century literary history and published a book on Norwegian novelist Sigurd Hoel. The main emphasis of his research is, however, Hans Christian Andersen. Mylius has had books published in Germany and China as well as articles in a host of languages.

His most recent books include "The Price of Transformation – Hans Christian Andersen and his Fairy Tales" (2004, new edition 2005) and HCA. "Et livs digtning" (2005, an 860-page anthology using modern spelling and with introductory commentaries).

Photo: Erik Aavatsmark

Season's Greetings and

best wishes for the New Year

Domicile

The history of Lassen Ricard dates back to 1986

At the outset, Lassen Ricard was based on the top floor of “Peberbøssen” at 61 Østergade, at the corner of Strøget and Højbro Plads; in 1992, Lassen Ricard moved to “Hofkonditor Zieglers Gård” at 12 Nybrogade; and in November 2002, we moved to our current address at 31 Amaliegade, our largest and most impressive domicile so far.